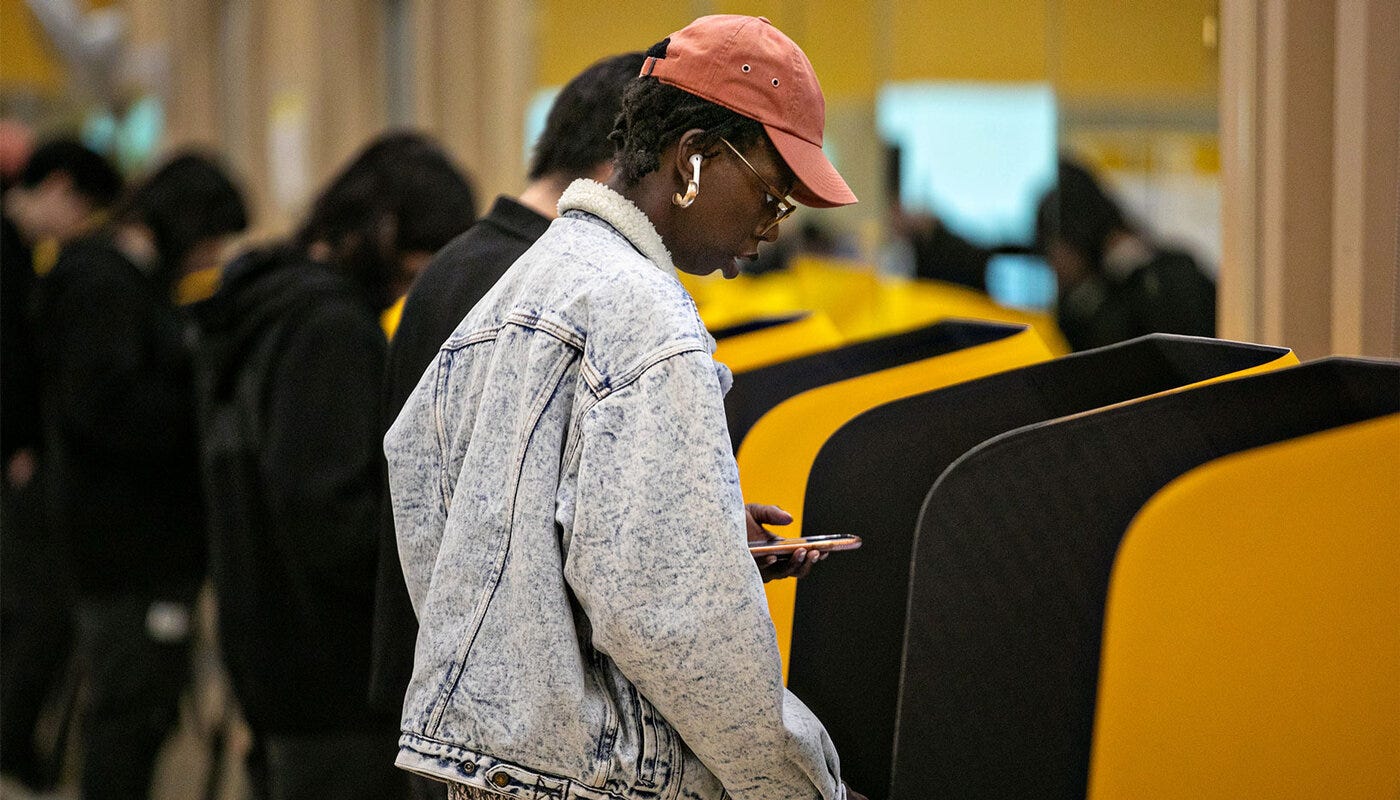

What Will Be Left of the Voting Rights Act?

The Supreme Court’s conservative supermajority returns to one of its favorite victims.

June is the cruelest month. Today begins the weeks of decisions to be announced by the Supreme Court as its term draws to a close. Once again we will wait to find out how far the six conservative justices will push — and what kind of country we will live in. I discuss the perils of this moment in my new book, The Supermajority, out next Tuesday.

One of the most important rulings will come in a major case on the Voting Rights Act, Allen v. Milligan. It could also be one of the most damaging. That statute was by some measures the most effective civil rights law on the books. And over the past decade, the Court led by Chief Justice John Roberts has demolished it, bit by bit.

The background of the Voting Rights Act will be familiar to readers of this newsletter. Although the 15th Amendment, ratified in 1870, guaranteed Black Americans the right to vote, states found countless ways to deter, dilute, and deny those votes for nearly a century.

Then came Bloody Sunday. Violent attacks on civil rights protesters horrified the nation, awoke a collective sense of justice, and galvanized our political leaders to act. On August 6, 1965, less than five months after the march, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law. It created our modern, multiracial democracy — an American success story.

But in the early 1980s, a young lawyer in the Reagan administration named John Roberts furiously opposed a bill renewing and clarifying the act. He lost that battle, but his war on the law was just beginning. He would in many ways make his crusade against the Voting Rights Act the signature issue of his career.

First came Shelby County v. Holder in 2013. The law’s Section 5 required states with a history of racial discrimination to get permission from the Justice Department or a federal court before changing voting practices. At the argument, Antonin Scalia called this a “racial entitlement.” The audience gasped. Scalia did not write the opinion, though; Roberts did, and he was more decorous. The South had changed, he explained. That was then, this is now. The Court effectively ended Section 5.

Within hours, states began to implement discriminatory voting laws. Texas, for example, implemented a voter identification law that instantly disenfranchised 608,000 registered voters, according to a federal judge.

Weak and wobbly, there was something left of the Voting Rights Act: Section 2. That lets you sue after the fact to prove discriminatory voting practices. Voting rights groups including the Brennan Center began to use it to challenge the new wave of voter suppression laws — with heartening success. We won our case against the Texas law, for example. Then in 2021, in Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee, the Court made it much, much harder to use Section 2 against discriminatory voting laws.

All of which brings us to the upcoming case. For decades, Section 2 has been a potent protection against racial gerrymandering, the drawing of legislative lines to dilute the power of the vote for communities of color. In fact, challenging gerrymandering is the main way Section 2 has been used before. That law’s strength may soon be a memory.

In the case, Alabama’s mapmakers packed as many Black voters as possible into an already existing majority-black district, then surgically distributed the remainder among other districts to ensure that they could not assert political power. Black voters could elect a candidate of choice in only one of seven districts despite making up over a quarter of the state’s voting age population. The Court may bless that. (Talk about “racial entitlements”!)

Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote a memorable dissent in Shelby County. She warned, “Throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.” In the decade since, the white-Black voter turnout gap grew between 9 and 21 percentage points across five of the six states originally covered by Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act. Maybe other factors caused this gap to grow. But an eviscerated rights law surely won’t help.

On many things, John Roberts has been prudent, canny, an institutionalist. When it comes to the law of democracy, he has been the activist leader of a disciplined conservative cadre. The supermajority, I fear, is just getting warmed up.

IMAGE: Jason Armond/Getty